The massive translucent cones sliding down the sides of the Guggenheim Museum in Abu Dhabi are finally visible to passersby whizzing through the city’s highway. It’s set to be about 12 times the size of its New York counterpart.

Nearby, soaring metal structures resembling falcon wings sit atop the roof of the new Zayed National Museum, just miles from an upcoming natural history museum and a branch of the Louvre that opened in 2017.

There are growing signs of a massive construction boom changing the face of this once sleepy, oil-rich emirate, which holds about 6% of the world’s crude reserves under its sands and controls $1.5 trillion in sovereign wealth.

Sprawling theme parks, five-star hotels, luxury homes, sports complexes, and high-end office towers are rising at breakneck speed as the city’s rulers spend billions to diversify the economy and cater to global financial giants like Brevan Howard Asset Management and Greg Coffey’s Kirkoswald Asset Management, who’ve set up here.

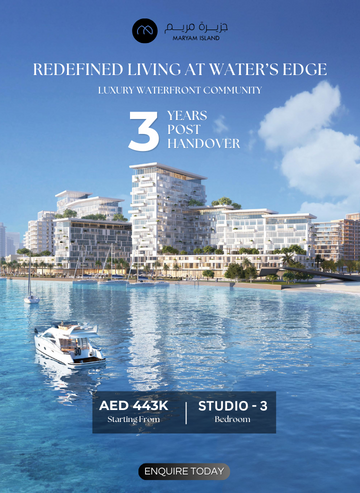

The Guggenheim is part of a more than $10 billion push to boost tourism and cultural activity in the emirate, the capital of the United Arab Emirates. In the meantime, Abu Dhabi is also pouring billions more into building sprawling residential developments to attract rich expatriates to live and work here. Wealthy buyers from the UK, India, Spain, and beyond are snapping up seaside villas costing millions.

There are challenges to the desert city’s big ambitions. The Middle East is heating up at one of the world’s fastest rates and while the UAE is among the countries that have pledged to reduce emissions, there are concerns parts of the Gulf could become too hot for people over the coming decades. The region can also be volatile — the Israel-Hamas war, now in its 11th month, still threatens to spill over into a wider conflict.

Still, the UAE’s rulers, who are already using their oil wealth to wield more international power, want a city that showcases this heft.

“Abu Dhabi is trying to position itself as a global hub, not just a regional hub,” said Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, an Emirati columnist, art collector, and member of the ruling family of the emirate of Sharjah. “It’s building the physical infrastructure that goes with its global ambition as the capital of a country that’s punching above its weight not just economically, but also politically and culturally.”

Attempts to create international hubs in the Middle East have had mixed results. Doha spent hundreds of billions of dollars to prepare for the football World Cup and aimed to transform itself into a regional tourism hotspot, but is now grappling with an oversupply of hotel rooms. Saudi Arabia planned to build the new city of Neom for more than $500 billion but has pared back some goals amid funding limitations.

Dubai, meanwhile, built all the trappings of a global metropolis over a few decades and is widely regarded as a success story. Still, an influx of expatriates since the pandemic has taken its toll on the city’s infrastructure. Roads around the financial center are routinely packed and waiting lists for schools run long. The emirate’s vulnerability to climate change was also on display in April amid unusually heavy rains that brought it to a standstill. (Abu Dhabi is a network of islands and that helped drain some of the floods, but it also experienced significant water logging.)

The UAE is a federation of seven sheikhdoms that includes both Dubai and Abu Dhabi and was formed in 1971. Oil was discovered in the capital in the late 1950s, helping transform the country — then, a backwater populated by just over 100,000 people beyond recognition.

In the decades that followed, it was Dubai that emerged as the regional hub, with its open-for-business approach attracting the most influential names in finance. Abu Dhabi took a more staid approach for years, though that’s now changing. Its quest for new residents also coincides with Riyadh’s increasingly aggressive expansion push, setting the stage for a three-way tussle for talent.

Unlike Saudi Arabia, which is pressuring firms to set up regional headquarters in the kingdom or risk losing business, Abu Dhabi is taking a different approach. Officials are quietly orchestrating a package of perks they hope will help propel the city up the ranks of the world’s biggest financial centers. A horde of firms have already rushed in, leading to a shortage of office space.

Abu Dhabi first started building on Saadiyat and Yas islands in 2005. Work on some projects stalled in the aftermath of the global credit crisis and the problems worsened during the 2014 oil crash. After the pandemic, property prices rebounded from a lengthy stagnation as international banks, hedge funds, and traders arrived in the UAE to capitalize on low taxes and easy residency.

Zero income tax helped lure wealthy families seeking to avoid rising taxes in Europe, and the country has widened the pool of residents eligible for 10-year residency. A survey by real-estate agency BetterHomes shows that British nationals were the biggest purchasers of Abu Dhabi residential property in the first half of 2024, followed by buyers from the UAE, India, Spain, Turkey, and the US.

Still, expats without citizenship rights make up more than 80% of the UAE’s population, which could add a layer of uncertainty.

“People and capital are fickle and they can move on to the next shiny thing,” said Sarah Moser, a professor at McGill University and director of the New Cities Lab. “Just because you build it, it doesn’t necessarily mean people will come forever. They may come for the first years or decades, but people are very mobile and without offering citizenship people and capital can move.”

“A hundred years in the future, I wonder what’s going to remain of all of this,” Moser said.

Those potential challenges haven’t stopped buyers. Demand is surging and prices for villas on Saadiyat island — favored by wealthy investors looking for beachside penthouses — rose nearly 15% in the first quarter from a year earlier and rents climbed 6.4% in the same period, according to CBRE Group Inc. Meanwhile, occupancy in Abu Dhabi’s financial center has reached 95%.

Developers are rushing to capitalize on the demand. Nestled among mangroves, Abu Dhabi’s Jubail Island is bustling with cranes and workers. They’re constructing a $4 billion community that spans 2,800 hectares and will house about 10,000 people in low-density villages. It will include schools, clinics, gyms, and other facilities. Waterfront mansions can sell for as much as $18 million.

On nearby Ramhan Island, a developer owned by royal family members is building 1,800 mansions and 900 homes. A luxury Ritz Carlton resort is being built on stilts, Maldives style.

A hill that’s 50 meters high is being mounted at the center of Hudayriyat Island, where luxury homes will be perched in a cascading formation resembling the Greek island Santorini. Some will be open for sale to foreign buyers, something that is restricted in many parts of Abu Dhabi.

“Dubai was the showier emirate,” Moser said. “But that changed in recent years and now Abu Dhabi has a completely different strategy. It’s all about attracting international investment and diversifying the economy.”

Developers are expected to complete the construction of 8,660 homes in Abu Dhabi this year. They’re also expected to hand over 56,000 square meters of office space mostly in Masdar Square, a low-carbon city built in Abu Dhabi, during the same period.

Still, as Abu Dhabi expands its infrastructure, the demand for energy to cool buildings in one of the world’s hottest regions will grow more acute and stand in direct conflict with the government’s sustainability commitments. The UAE, which is one of the world’s highest emitters of greenhouse gasses on a per capita basis, hosted COP28, the United Nations Climate Conference last year. That momentum will prove critical as the planet continues to warm, with countries in the Gulf heating up about twice as fast as the global average.

Sustainable building design will become vital amid the need to reduce energy use in a region where up to 70% of electricity goes to cooling homes.

Abu Dhabi’s strategy of expanding the population could carry risks because it depends on the availability of cheap oil for the energy needed to cool homes and offices in an ever-heating world, Moser said.

As the real estate market rebounds, projects that were put on hold during the financial crisis are being revived. The Guggenheim is finally taking shape nearly 20 years after architect Frank Gehry first unveiled the design. Abu Dhabi is also building hospitals and schools to service the new residential communities. Gordonstoun, the Scottish boarding school where King Charles was educated, is planning to open its first campus in the Persian Gulf on Abu Dhabi’s Jubail Island in 2026.

“Where else would you walk out of the Louvre and into a Guggenheim in a few minutes,” Al Qassimi said.

The central idea is to make the city attractive to people from all parts of the world. Saadiyat Island now has a complex encompassing a mosque, a church, and a synagogue.